If you’re familiar with Wagner’s anti-Semitic politics, Tannhäuser might seem an odd choice of entertainment for the founder of political Zionism.

By Ben Kaplan, The Algemeiner

To understand Theodor Herzl, it’s helpful to think about opera.

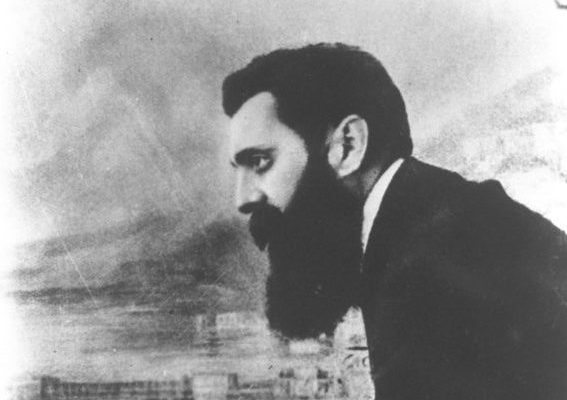

In the summer of 1895, a distraught Herzl wandered the streets of Paris, contemplating the fate of the Jews. In January, he had witnessed the degradation (public shaming) of Alfred Dreyfus, and in April, the rise of an antisemitic party to power in his home city of Vienna. In June, he began his Zionist diaries.

Herzl’s only consolation during those hot summer nights in Paris was the opera. He attended performances at the Paris opera of Wagner’s Tannhäuser, and during this same time, he formulated his scattered thoughts into a plan to save the Jews of Europe, which he later published as The Jewish State.

If you’re familiar with Wagner’s anti-Semitic politics, Tannhäuser might seem an odd choice of entertainment for the founder of political Zionism; in fact, Wagner was — despite his well-known political views — beloved by German-speaking Jews of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

That tension between art and politics, between German-speaking and Jewish identity, characterizes the complexity of Herzl’s life and identity: an Austrian and a Jew — a man of the theater, and a man of politics.

In Herzl’s mind, the latter two were closely linked: politics was theater. Desperate to become a playwright, he eventually finds success as a journalist before devoting himself to the cause of Zionism. But even after this transformation, he never ceases to think of himself — or life, for that matter — in theatrical terms.

The Herzl one encounters at the First Zionist Congress is a theater impresario par excellence, dictating all aspects of the mise-en-scene, insisting, most famously, that everyone in attendance dress in black tie, complete with top hats and tails. “I am still as ever the dramatist in all this,” he writes in his diary. “I take poor, destitute people off the street, dress them in wonderful clothes, and have them perform before the world a marvelous play of mine.”

The opera I’ve written with composer Alex Weiser, State of the Jews, focuses on the last year of Herzl’s life and explores this history. We are often asked why we chose to write an opera about Herzl, and the truth is that Herzl himself was already larger than life — operatic.

In the span of a few years, he met with an emperor, a sultan, and a pope; he mobilized a mass political movement made up of thousands upon thousands of devoted followers (and many critics); and like Moses, he died before reaching the Promised Land.

His wife Julie — as crucial a character in our opera as he is — and their three children all died tragic deaths after him. In their lifetimes, there was little redemption to be found.

But why was Herzl so obsessed with opera? To begin with, it would have been one of the most exciting forms of popular entertainment in his time. And Wagner, with his emphasis on creating an immersive, emotional experience filled with mythology and grandeur, was the captivating avant-garde artist of his era. So too does content dictate form: a big idea requires an epic format; opera, with all its idiosyncrasies, deals with grandeur.

Herzl drew inspiration from the opera for his big idea, and our opera, State of the Jews, grapples with the meaning of that history. Rather than take a stance on the political issues at play, the opera seeks to dramatize the costs of pursuing such a big idea, to show the collision of the personal and the political. Julie Herzl, a woman mostly lost to history, emerges in this opera as someone struggling to maintain her individual dignity and agency amidst unimaginable difficulties. The question we’ve asked ourselves is: if history cannot redeem her, can art?

I find myself drawn to Herzl’s naivete, perhaps foolishly. Despite his personal flaws — and there were many — he saw his project not, as many may believe, as a purely tribalistic enterprise. Rather, he believed Jewish emancipation would “react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity,” as he writes at the end of The Jewish State. That might seem naive to some today — to imagine we could transcend our tribal affiliations of politics and background and come together for the sake of mutual benefit. But is it?

Herzl wasn’t just insistent about top hats for their style — he saw the staging of identity as a chance to assert individual dignity. Maybe we too could assemble — say, at the opera, or some other hall — across our differences, and envision something new.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, librettist Ben Kaplan studied literature and theater at Williams College. He currently serves as Director of Education at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, where he directs programs that teach Jewish history and culture to a broad and diverse audience.