Krug wasn’t black or “Latinx.” Nor was she from “El Barrio.” Instead, she was a middle-class white Jewish woman who grew up in suburban Kansas City and attended a day school.

By Jonathan S. Tobin, JNS

Great imposters are the lifeblood of “stranger than fiction” stories that are hard to resist. Tales of troubled people who find it difficult to live life in their own skin and con their way through life pretending to have other identities and professions always fascinate audiences.

That was true of Leonardo DiCaprio’s portrayal of real-life trickster Frank Abegnale in Steven Spielberg’s film “Catch Me If You Can,” which delighted audiences and critics alike when it came out in 2002. The viewer knows the protagonist is a liar, thief and insincere seducer. Yet we still root for him to get away with it. We do so in part because we like the actor playing him, but also because there’s a part of all of us that longs to shuck our true identities and become someone else.

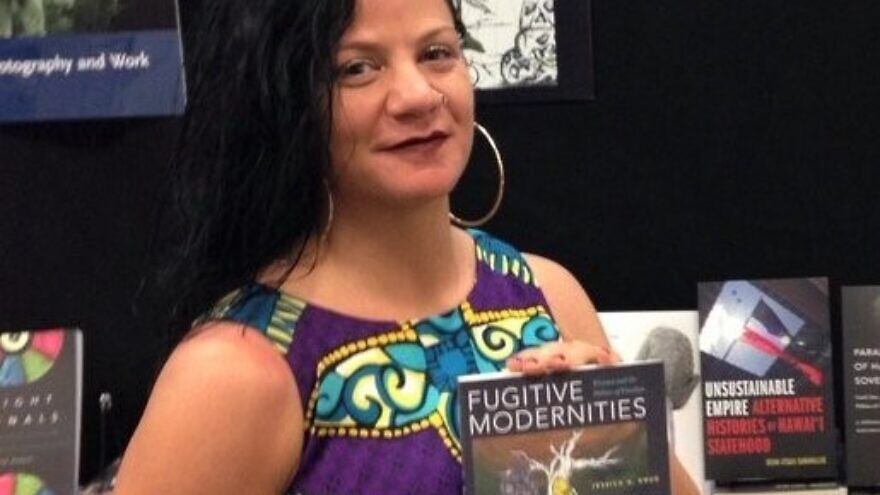

But that’s not how the world has reacted to the revelation that Jessica Krug, a tenured associate professor of history at George Washington University, had spent her career pretending to be someone she isn’t.

Her colleagues and students, as well as the editors of magazines and journals where her writing was welcomed, were under the impression that Krug was a black and Hispanic woman from “El Barrio” in the Bronx, N.Y. They believed her story about fighting systemic racism and becoming an outspoken and aggressive critic of white racism who honored her African and Caribbean “ancestors” with her radical activism.

She wasn’t just honored for her scholarship, in which she put leftist dogma about race to work. She also purported to be an expert on salsa dancing and a spokesperson for inner-city minorities whose contempt for liberal whites who purported to be sympathetic to her “black and brown siblings” knew no bounds.

But as it turns out, Krug wasn’t black or “Latinx.” Nor was she from “El Barrio.” Instead, she was a middle-class white Jewish woman who grew up in suburban Kansas City and attended a day school.

Krug isn’t the first black impersonator to make the news. In 2015, Rachel Dolezal, the chapter president of the NAACP in Wichita, Kan., was revealed to be white. Dolezal had to resign from the group, but still maintained that she had a right to self-identify as black even if that didn’t conform to her actual ancestry.

Though it seems utterly fraudulent in a society where gender is now considered fluid and a matter of choice rather than a function of biology, it might be possible to assert such a claim when it comes to race. But at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement has ascended to a position of cultural dominance and “cultural appropriation” has become a capital offense in the eyes of many, blacks and whites alike reject Dolezal’s claims as offensive.

But what makes Krug’s journey from the Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy in Overland Park, Kan., to East Harlem and GWU is not just that she was a white woman pretending to be black, but that along the way she more than rejected her Jewish identity. As part of what can only be termed a modern-day leftist version of a minstrel show, Krug also incorporated attacks on Jews and Israel in rants in which she vented her rage as an aggrieved person of color.

Krug testified at a virtual New York City Council hearing in June in which she excoriated the police, liberal politicians and white sympathizers. She did so under the name of “Jess La Bombelara” — literally, “Jess the bombshell” in Spanish — which we are now told was the “salsa name” she used when she posed as a dance and movement “expert.”

Speaking in what sounds like a parody of a Bronx Hispanic accent, the “bombshell” denounced white citizens, who had also waited their turn to testify, for not yielding their time to blacks and Hispanics like her.

And in a profanity-laced speech about the evils of a police department that she said needed to be abolished, she also found time to falsely claim that the NYPD was being trained by the Israel Defense Forces in “counter-insurgency methods” in order to harm blacks. That echoed other things she has written in which she denounced Jews for oppressing the “indigenous” people of “Palestine.”

It’s one thing to pretend to be someone you’re not. Krug, however, upped the ante by not only denying her own heritage, but also spreading blood libels about fellow Jews.

Doubtless, Krug’s inner demons help explain her aberrant behavior. In a blog post in which she confessed her fraud — reportedly motivated by the fact that she was about to be outed by suspicious colleagues — Krug wrote repeatedly of having mental-health issues and unspecified childhood trauma that caused her to flee her “lived experience as a white Jewish child in suburban Kansas City.”

But what is interesting about her case is the way a universal desire to be someone else was incorporated into false narratives about white privilege and systemic racism. What made her new identity so attractive to Krug and those who fell for it was that it gave her a chance to be both exotic and a victim. That made her far more interesting and fashionable than being a normal white kid growing up in the Midwest.

There was once a time when being Jewish would have satisfied both the desire for exoticism and victim status. Jewish women are depicted throughout 19th-century English literature as the epitome of the glamorous outsider.

In Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe,” it is the exotic and beautiful Jewish healer Rebecca who makes the Anglo-Saxon heroine nervous about losing the affections of the hero. The same role is played in Anthony Trollope’s parliamentary novels by his character Marie Goesler (a rare sympathetic Jewish character from a novelist who created more than his share of Jewish villains).

In George Eliot’s philo-Semitic and proto-Zionist “Daniel Deronda,” the beautiful heroine Mirah winds up getting her man (who discovers that he is really Jewish, too).

If victimhood is what you want, 20 centuries of anti-Semitism would have seemed to permanently confer that title on the Jewish people. But in contemporary political culture, being Jewish means laboring under the alleged burden of “white privilege” and buying the big lies that Jews aren’t indigenous to the land of Israel. That’s what Jewish leftists say while operating under the banner of anti-Zionist groups like Jewish Voice for Peace and IfNotNow.

Krug didn’t have to invent an identity to teach or write about Africa or Hispanic culture. But doing so enabled her to become a more authentic victim who was entitled to lecture the rest of us about our alleged racism.

Her antics are infuriating to actual black people, who not unreasonably consider her actions a form of cultural theft. Yet what helps make it understandable is that by pretending to be black and Hispanic, she achieved the kind of status that being Jewish no longer supplies in a culture in which Jews are considered merely a different kind of white oppressor.

More than anything, Krug is guilty of giving leftist dogma exactly what it craves — an angry person of color denouncing whites and Jews in the name of black victims, even though she lacked the standing to play that role.

In playing a stereotype, she was also being one: a self-hating Jew who had to attack her own people and abandon her past all in order to believe that she had value as a human being.

Though what Krug did was beyond the pale, the difference between pretending to be a black person who attacks Jews and being a Jew who also denies Jewish rights while operating under the banner of anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic Jewish groups is not as great as they’d like to think.

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor in chief of JNS—Jewish News Syndicate. Follow him on Twitter at: @jonathans_tobin.