A Jewish family made their home in Canada’s far north and found allies of Israel in the unlikeliest places.

By Dan Brotman, TheJ.ca

In 1978, Lorne and Sheila Levy were a newly married couple in their mid-20s, with an appetite for adventure. Lorne, a native of Toronto, graduated with a Bachelor of Education, specializing in industrial arts, in addition to a Bachelor of Applied Arts in radio and television production from Ryerson, and Ottawa-born Sheila was a primary school teacher.

When the couple was offered the opportunity to move to the far north and teach in Pangnirtung, an Inuit hamlet located on Baffin Island, in what is today Nunavut, they accepted. “Nunavut,” meaning “our land” in Inuktitut, officially separated from the Northwest Territories in 1999 and is Canada’s newest territory.

At the time that they accepted the offer to teach in Pangnirtung, Sheila says, “we had no idea of where it was, or what it looked like.” The community of a thousand residents, almost all of whom were Inuit, recruited the pair to teach a combination of shop, home economics, and a primary school class.

What first struck them about the area was its physical beauty. “I had never seen mountains until we moved there so that in itself was extraordinary,” recalls Lorne. Located on a fjord, the mountains around the town towered over a mile high, and the nearby Auyuittuq National Park served as the backdrop for the opening scene of the 1977 James Bond thriller The Spy Who Loved Me.

Despite being double minorities, as both the only Jews and two of 40 non-Inuit residents, “the community was very different from anything we had ever experienced. The Inuktitut language was very vibrant, and living there allowed us the opportunity to experience things we never would have otherwise,” says Lorne.

They felt instantly welcome in the community and acquired a new-found love for outdoor activities such as hunting, fishing, and camping. Lorne used these expeditions with locals to learn Inuktitut, which they would speak in his presence. Even when teaching, he insisted that his students speak to him in their native tongue, rather than English. The couple employed a local babysitter to look after their young daughter, from whom she acquired native fluency in Inuktitut. During their last two years in Pangnirtung, another Jewish couple had moved into the community, and the Levys, their young daughter, and the other Jewish couple celebrated Chanukah and Passover together.

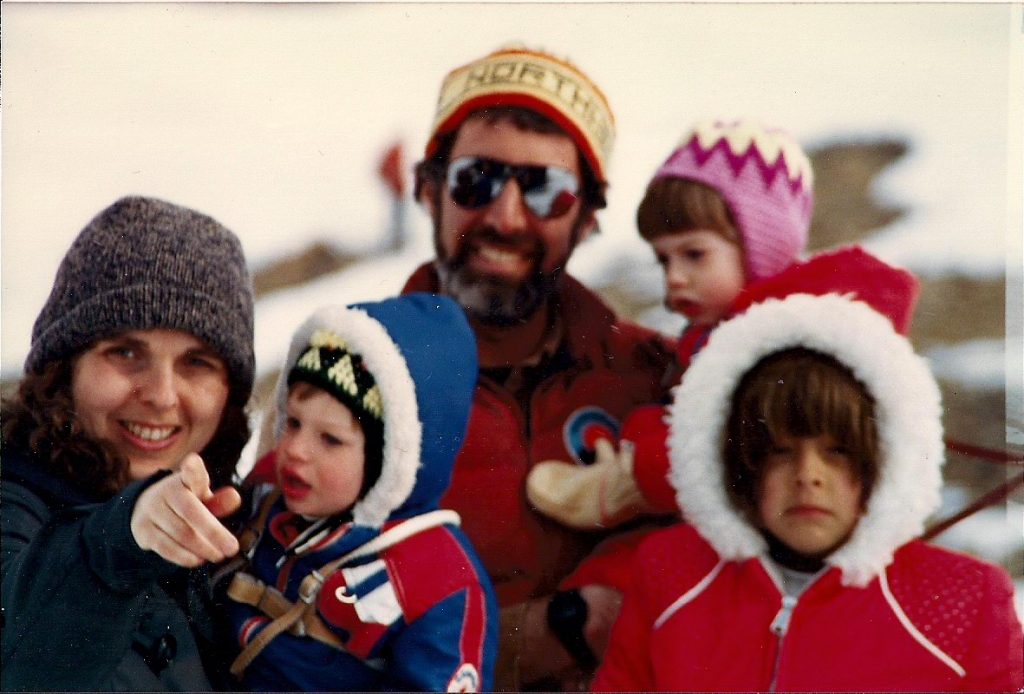

In 1982, their young family relocated to Gjoa Haven, an even smaller community above the Arctic Circle. The town was home to only 700 residents, and in the winter experienced 24 hours of darkness, with lows reaching -40 degrees Celsius. During their four years in Gjoa Haven, Lorne served as the local school principal, and Sheila gave birth to twins. They both reminisce of how the locals would fawn over their three children, who were the first-ever non-Inuit children to live in the community. Life in Gjoa Haven primarily consisted of socializing at each other’s homes. “When you live in a small community, your friends become your family,” says Sheila.

In 1984, the young family moved to Cambridge Bay, also in the central Arctic and north of the Arctic Circle. Lorne assumed the role of superintendent of schools and Sheila returned to teaching. The Levys stayed in this community for three years, and then permanently settled in Iqaluit, which is today the capital and largest city in Nunavut.

It was upon moving to Iqaluit that they finally purchased a car, having relied exclusively on snowmobiles for transportation during the previous nine years. There were several Jewish families living in Iqaluit at the time, with whom they would get together to celebrate holidays. The Levys became well known in the local community for their Chanukah parties, which some years attracted up to 100 local community members. These parties became so renowned in Iqaluit, that one year a hotel even offered to host their party on their premises, for a nominal charge.

First Bar or Bat Mitzvah in Nunavut

The Levy twins were the first children to ever have a bar or bat mitzvah in Nunavut. Lorne’s sister-in-law, a rabbi in Toronto, helped the family plan an inclusive b’nai mitzvah ceremony. So many members of the wider Iqaluit community attended the ceremony, where their son presented a comparison on the founding of Nunavut with that of the State of Israel, and their daughter presented on strong Jewish women throughout the ages.

“The Inuit have a great fascination with and respect for Jewish culture,” observes Lorne. “Over the years, I can think of countless times when people would respectfully want us to know that they knew we were Jewish, and that they were friends of Israel.”

He eventually worked in local government and assumed the role of the territory’s assistant deputy director of Infrastructure and Capital Programming. On a visit to a member of the Legislative Assembly’s home community, Lorne noticed an Israeli flag hanging inside the politician’s home. When he inquired as to why the assembly member hung an Israeli flag, his host responded, “the Inuit are friends of the people of Israel.” This compelled Lorne to reveal that he is Jewish, to which the gentleman surprised him by responding, “Of course we know you are Jewish!”

Although all three of their children moved to Ontario for their university education, two of the three returned to Iqaluit to start their own families. Their son met his wife on a trip to Israel, and despite her trepidation about living in such a remote region, he successfully convinced the native Torontonian to move back up north with him. When the couple had their first son, they flew up a mohel (Jew trained to perform circumcision) from Toronto, who performed Nunavut’s first-ever brit milah.

No regrets

Although Lorne and Sheila have since retired to Ottawa, they still spend several weeks a year back in Nunavut. Sheila has no regrets about the couple’s decision to raise a Jewish family in one of Canada’s most remote regions.

“Nunavut is so amazingly different, and is a place that most Canadians will never get to experience. I wanted our kids to feel comfortable wherever they are in the world, so they can deal with diversity and differences. While they missed out on many experiences that they could have had growing up in Ontario, they gained so many experiences that they would not have otherwise had.”