“My advice on negotiating with Iran is to recognize that the United States has the upper hand. Recognize that the regime in Tehran is facing many serious pressures,” the U.S. Special Representative for Iran tells JNS.

By Jackson Richman, JNS

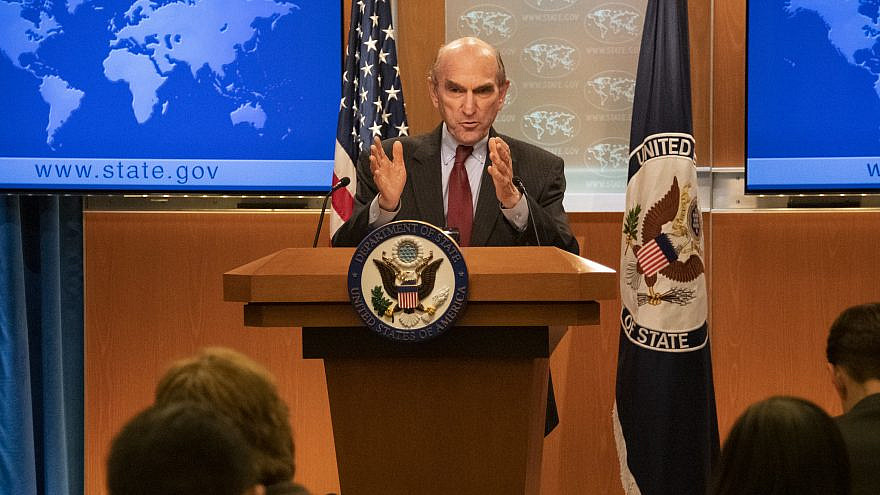

Elliott Abrams is no stranger to Washington, specifically U.S. foreign policy, having served in the Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush and Donald Trump administrations. He also served under longtime Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.), a stalwart supporter of Israel.

Abrams has also worked in the private sector, including at the Council on Foreign Relations, where he is currently on leave.

Abrams, 72, was named U.S. Special Representative for Venezuela in 2019, and a few months ago, took on the position of U.S. Special Representative for Iran, succeeding Brian Hook. The roles merged into the title of U.S. Special Representative for Iran and Venezuela. The portfolios are related, as Tehran and Caracas are allies, and have sought to engage in commercial oil and other trade—namely, through ship engagements coming to and from the Persian Gulf.

Since withdrawing in May 2018 from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—a significant part of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran has focused on cracking down on this relationship between the two rogue regimes. Over the years, a series of severe new sanctions have been enacted that have had a profound effect on Tehran’s economy, as seen in nationwide protests before the coronavirus pandemic hit earlier this year. Iran has been the hard-hit country in the Middle East with 1 million recorded cases of COVID-19 and 50,000 deaths as a result.

JNS talked with Abrams by phone on Dec. 8. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: While the Trump administration has significantly scaled up pressure on Iran, the fact is that the Islamic regime continues its pursuit of nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles and regional aggression. As such, would you consider the “maximum pressure” campaign to be a success?

A: Yes. The purpose of the campaign was to build leverage and can be used to force Iran to stop doing the many malicious things it’s doing. The president always said he anticipated a negotiation with Iran, and the purpose is to build leverage for that negotiation, and we’ve got it. We were very critical of the JCPOA for many reasons, one of them the short sunsets. But another that it covered nuclear activities only. It didn’t cover their missile program. It didn’t cover Iran’s support for terrorism and its many malign activities throughout the region. How do you get Iran to stop doing all of that when they don’t want to? The answer is you need to build up a lot of pressure on them. The leverage is there, which means the campaign has succeeded. Now the question is how that leverage will be used.

Q: Aside from sanctions, what more can be done to change Iran’s behavior?

A: There needs to be a lot of international coordination. Without the “maximum pressure” campaign, I think you would not be seeing the kind of coordination in cooperation you are seeing between Israel, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates. That’s very important. We also need coordination with the Europeans, particularly the British, French and Germans, who were involved in the negotiation with Iran in 2015, to keep the pressure on the IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency]. So there are a number of places you need to keep the pressure on in the region, and you need to keep it on the IAEA about nuclear activities. And you need to keep the economic pressure on.

Q: What measures is the administration putting in place in terms of Iran-Venezuela relations that would make it more complicated to take sanctions off on both states, and would make it difficult to treat Venezuela the same way the Obama administration treated Cuba?

A: First, we have the sanctions programs both for Iran and for Venezuela. Second, the nature of the sanctions varies. There are human-rights sanctions, nuclear-related sanctions, terrorism-related sanctions. Some sanctions are very easy to delist and others are not because Congress really established the criteria in legislation—for example, terrorism sanctions. How can you lift terrorism sanctions if the terrorist activity is continuing? So I think we have a broad array of sanctions on both Iran and Venezuela.

You may remember the seizure of several tankers that were carrying gasoline from Iran to Venezuela. We’ve made it clear to ship owners, ship captains, ship insurers that we will go after those that engage in that trade, which doesn’t eliminate it, but it means that it is, first of all, limited physically to only Iranian oil tankers. The Iranians make efforts to hide what’s going on. Ships are involved in changing their names, or they turn off their transponders so they can’t quite tell where they are. They do ship-to-ship transfers in an effort to hide the origin and the destination. All of which costs them money and reduces the revenue to the regime in Caracas, which is one of our central goals. When they sell crude oil, they have to sell it at an enormous discount and that clearly reduces their income.

Q: Do the latest withdrawals of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and Iraq create power vacuums for Iran to fill?

A: We don’t think so. We think that there are enough forces there both to protect our people and to continue to go after ISIS [the Islamic State] and other terrorist activities, which is their main focus. So we don’t think we are creating any kind of vacuum. I think it’s also true in the case of Iraq that there’s real resistance on the part of Iraqis to be ruled from Tehran.

Q: Do you think that President-elect Joe Biden will re-enter the United States into the Iran nuclear deal or, at the very least, give Iran sanctions relief?

A: President Donald Trump said he wanted to and expected to enter into a negotiation with Iran after Jan. 20. I’ve said for many months that no matter the outcome of the election, there would be some kind of negotiation with Iran.

Returning to the JCPOA is not like turning a light switch on, off, on, off. Five years have passed since the JCPOA was agreed upon. The first sunset has already come, the eventual arms embargo, and frankly, it’s unbelievable when you think about it that any American administration would have agreed to such a short timeline for Iran to be able to import and export really serious weaponry like advanced combat jets. And there are more sunsets coming in the next few years. You can’t just say, “OK, we’re back in JCPOA this morning.” The United States will have some demands of Iran, like exporting the enriched uranium that they now possess far in excess of what they agree to in 2015. And they’ll ask for sanctions relief. So that negotiation will be there.

My hope is that the next administration recognizes that we have the upper hand. Iran’s economy is reeling. Iran’s people despise this regime, as they showed in November of last year. There is no reason that we have to make all sorts of concessions to Iran. They are the ones who need relief. I hope the leverage that has been built up will be used and, obviously, we hope that there is not a return to the JCPOA. There is instead a much better agreement that lengthens those sunsets, and that covers the missiles and the support for terrorism, the aggression, the subversion in the region. I think there is a lot of support for that, including in Europe, where there is a recognition that the JCPOA fell short.

Q: What is your advice to the incoming Biden administration, which has indicated it would return to negotiations with Iran?

A: My advice on negotiating with Iran is to recognize that the United States has the upper hand. Recognize that the regime in Tehran is facing many very serious pressures. One of them the economic situation in the country. Another, its growing isolation in the region as we watched, for example, the Abraham Accords. Another, the rejection by the people of Iran. The Supreme Leader is quite old and has never been in great health now for years. So they may face a succession in the next few years. Put all that together, and they’re in a weak position, and we are in a strong position. We should use it in any negotiation.

Q: The Trump administration has treated Qatar as an ally. However, Qatar supports Iran and its proxies, including Hezbollah and Hamas. Doesn’t the administration’s favorable treatment of Qatar only undermine the “maximum pressure” campaign against the Iranian regime?

A: No one has benefited from the rift in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) except Iran. It had been U.S. policy ever since that rift happened, which I think was under the Obama administration, to try to get it patched up. Just to give you an example: If Qatari planes cannot overfly Saudi Arabia and instead have to overfly Iran on international flights, every single one of those brings a big fee to Iran, and we know what they do with any revenue they have. A good decent amount goes to their military and then to the IRGC [Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps]. So we have thought, now under two administrations, that ending that rift would be a desirable thing. We would like to see more unity among the GCC countries, recognizing and pushing back against any forms of Iranian conduct.

Q: Throughout your career, you’ve played a major role in major U.S. foreign-policy decisions. How have your current roles compared to your previous jobs? Have your current positions been your greatest challenge?

A: Oh, boy. The main difference is that previous positions have been very broad either global or involving a whole region, like all of Latin America or all of the Middle East. Now I’ve got two special focuses—Iran and Venezuela—and that’s both a great challenge and a great opportunity. It really allows you to dispense with a lot of secondary issues, as well as a lot of administrative and organizational issues that would otherwise be there. I’ve been enjoying the focus on just these two issues. I can’t say what’s the single greatest challenge, but there’s been no greater challenge than Iran because it involves terrorism on the part of the regime, and of course, it involves their nuclear-weapons program. It’s really extremely consequential for us and for the whole Middle East.